TPO December 9th, 2025.

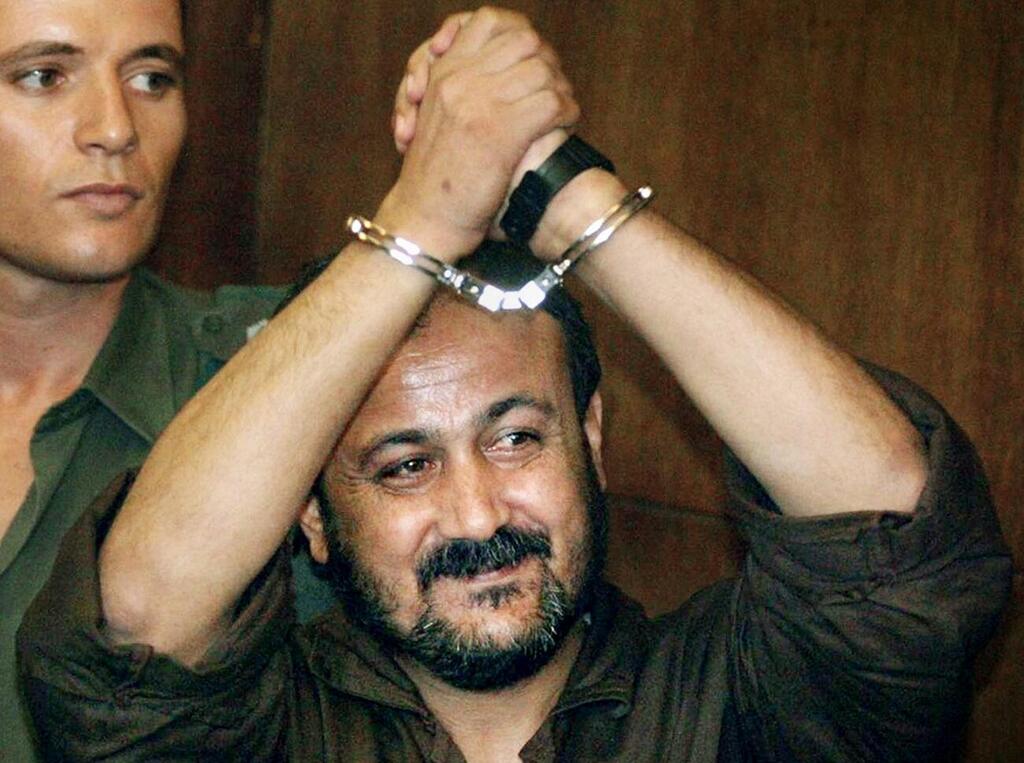

The first Intifada, (الانتفاضة الأولى) also known as the First Palestinian Uprising, was an uprising involving violent and non violent protests, riots, civil disobedience and military engagements carried out from the palestinian population and fighter, led by Marwan Barghouti.

The Intifada began on 9 December 1987, in the Jabalia refugee camp after an Israeli truck driver collided with parked civilian vehicles, killing four Palestinian workers, three of whom were from the refugee camp. Palestinians claimed that the collision was a deliberate response for the killing of an Israeli in Gaza days earlier. Israel denied that the crash, which came at time of heightened tensions, was intentional or coordinated.

The Palestinian response was characterized by protests, civil disobedience, and strikes, with Israeli occupation forces responding with brutal violence. There was graffiti, barricading, and widespread throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails at the Israeli army and its infrastructure within the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

These contrasted with civil efforts including general strikes, boycotts of Israeli Civil Administration institutions in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, an economic boycott consisting of refusal to work in Israeli settlements on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, and refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licenses.

The Uprising came as a natural response of the palestinian population to the repression endured from israeli rule, including beatings, shootings, killings, house demolitions, uprooting of trees, deportations, extended imprisonments, and detentions without trial.

After Israel’s capture of the West Bank, Jerusalem, Sinai Peninsula, and Gaza Strip from Jordan and Egypt in the Six-Day War in 1967, frustration grew among Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories.

Israel opened its labor market to Palestinians in the newly occupied territories, who were recruited mainly to do unskilled or semi-skilled labor jobs Israelis did not want. By the time of the Intifada, over 40 percent of the Palestinian workforce worked in Israel daily.

Additionally, Israeli expropriation of Palestinian land, high birthrates in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and the limited allocation of land for new building and agriculture created conditions marked by growing population density and rising unemployment, even for those with university degrees. At the time of the Intifada, only one in eight college-educated Palestinians could find degree-related work.

This was coupled with an expansion of a Palestinian university system catering to people from refugee camps, villages, and small towns, generating a new Palestinian elite from a lower social strata that was more activistic and confrontational with Israel. According to Israeli historian and diplomat Shlomo Ben-Ami in his book Scars of War, Wounds of Peace, the Intifada was also a rebellion against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Ben-Ami describes the PLO as uncompromising and reliant on international terrorism, which he says exacerbated Palestinian grievances.

A resistance operation conducted by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) called “Night of the Gliders” is considered to be the point which incited the population to erupt. The operation took place in northern Israel on 25 November 1987, in which two Palestinian guerrillas infiltrated into Israel from South Lebanon using hang gliders to launch a surprise attack. One fighter was tracked down and killed by Israeli occupation forces before entering Israel. The other managed to cross into Israel, shooting an army truck and entering a base, killing six soldiers and wounding at least seven others before being shot dead.

Israeli Occupation and Palestinian Resistance

Israel’s drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of resistance, but the administration, pursuing an “iron fist” policy of collective punishment including deportations, demolition of homes, curfews, collective punishment, and the suppression of political and educational institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

On 9 December, several popular and professional Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights in response to the deterioration of the situation. While they convened, reports came in that demonstrations at the Jabalya camp were underway and that a 17-year-old Palestinian had been shot to death by Israeli soldiers. He would later become known as the first martyr of the Intifada. Protests rapidly spread into the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Youths took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs. Palestinian shopkeepers closed their businesses, and labourers refused to turn up to their work in Israel. Israel defined these activities as ‘riots’, and justified the repression as necessary to restore ‘law and order’.

Within days the occupied territories were engulfed in a wave of demonstrations and commercial strikes on an unprecedented scale. Specific elements of the occupation were targeted for attack: military vehicles, Israeli buses and Israeli banks. None of the dozen Israeli settlements were attacked and there were no Israeli fatalities from stone-throwing at cars at this early period of the outbreak.

Equally unprecedented was the extent of mass participation in these disturbances: tens of thousands of civilians, including women and children. The Israeli security forces used the full panoply of crowd control measures to try and quell the disturbances: cudgels, nightsticks, tear gas, water cannons, rubber bullets, and live ammunition. But the disturbances only gathered momentum.

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed, while no Israelis died. 77 were shot dead, and 37 died from tear-gas inhalation. 17 died from beatings at the hand of Israeli police or soldiers. During the whole six-year intifada, the Israeli army killed from 1,087 to 1,204 (or 1,284) Palestinians, 332 being children.

Tens of thousands were arrested (some sources said 57,000; others said 120,000), 481 were deported while 2,532 had their houses razed to the ground. Between December 1987 and June 1991, 120,000 were injured, 15,000 arrested and 1,882 homes demolished. One journalistic calculation reports that in the Gaza Strip alone from 1988 to 1993, some 60,706 Palestinians suffered injuries from shootings, beatings or tear gas.

In the first five weeks alone, 35 Palestinians were killed and some 1,200 wounded. Some regarded the Israeli response as encouraging more Palestinians into participating. B’Tselem calculated 179 Israelis killed, while official Israeli statistics place the total at 200 over the same period. 3,100 Israelis, 1,700 of them soldiers, and 1,400 civilians suffered injuries.

By 1990 Ktzi’ot Prison in the Negev held approximately one out of every 50 West Bank and Gazan males older than 16 years. British MP and author Gerald Kaufman remarked: “Friends of Israel as well as foes have been shocked and saddened by that country’s response to the disturbances.”

In an article in the London Review of Books, John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt asserted that IDF soldiers were given truncheons and encouraged to break the bones of Palestinian protesters. The Swedish branch of Save the Children estimated that “23,600 to 29,900 children required medical treatment for their beating injuries in the first two years of the Intifada”, one third of whom were children under the age of ten years.

Hamas was also part of the Intifada, despite being founded only 5 years prior. The organization both participated in protests organized by the UNLU and organized its own protests, mainly organizing around mosques. They also engaged in armed resistance operations targeting Israeli occupation soldiers.

During the 1st year of the Intifada there were only 10 attacks which were limited to detonating explosives and shooting at patrols, but over time these attacks increased in frequency with the 2nd year seeing 32 attacks including the kidnapping of 2 Israeli soldiers within the Green Line. In response to this Israel began to arrest and target many Hamas leaders including Martyr Leader and Founder Ahmad Yassin, but by this point Hamas had grown and was able to survive these attempts.

Palestinian Islamic Jihad also took part in the Intifida, although they had only 300 members. They took part in armed resistance and civil disobedience. Its main activity was throughout 1987, although they took a hit in 1988 when occupation authorities arrested most of its leaders they were able to regroup. In the modern times they played a significant role assisting Hamas in the 2023-2025 Gaza War against Israel.

Gaza during the Uprising.

UN’s Reactions

The large number of Palestinian casualties commenced international condemnation. In subsequent resolutions, including 607 and 608, the Security Council demanded Israel cease deportations of Palestinians. In November 1988, Israel was condemned by a large majority of the UN General Assembly for its actions against the Intifada. The resolution was repeated in the following years.

On 17 February 1989, the UN Security Council drafted a resolution condemning Israel for disregarding Security Council resolutions, as well as for not complying with the fourth Geneva Convention. The United States, put a veto on a draft resolution which would have strongly deplored it. On 9 June, the US again put a veto on a resolution. On 7 November, the US vetoed a third draft resolution, condemning Israeli violations of human rights

On 14 October 1990, Israel openly declared that it would not abide Security Council Resolution 672 because “it did not pay attention to attacks on Jewish worshippers at the Western Wall“. Israel refused to receive a delegation of the Secretary-General, which would investigate Israeli violence. The following Resolution 673 made little impression and Israel kept on obstructing UN investigations.

Outcome

The Intifada was recognized as an occasion where the Palestinians acted cohesively and independently of their leadership or assistance of neighboring Arab states. It transformed the conflict, helping bring about the Madrid Conference of 1991 and the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993

The success of the Intifada gave Arafat and his followers the confidence they needed to moderate their political program. At the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algiers in mid-November 1988, Arafat won a majority for the historic decision to recognize Israel’s legitimacy, accept all the relevant UN resolutions going back to 29 November 1947, and adopt the principle of a two-state solution based on 1967 borders.

The Intifada broke the image of Jerusalem as a united Israeli city. There was unprecedented international coverage, and the Israeli response was criticized in media outlets and international fora. The impact on the Israeli services sector, including the important Israeli tourist industry, was notably negative.